For gay and bisexual men, prostate cancer, in particular, can be even more challenging than for their straight counterparts. “Gay & Bisexual Men Living with Prostate Cancer (from Diagnosis to Recovery)” is a new book that addresses bias against and the unique needs of gay and bisexual men diagnosed with prostate cancer.

by B. R. Simon Rosser and William West

Edited by Jane M. Ussher, Janette Perz B.R., and Simon Rosser “Gay & Bisexual Men Living with Prostate Cancer” was written not only for the medical community treating gay and bi men with prostate cancer but also as a supportive resource for gay and bi men diagnosed with prostate cancer. It is the most current and comprehensive book on the subject published to date, incorporating the tremendous new developments in cancer treatment from the past ten years.

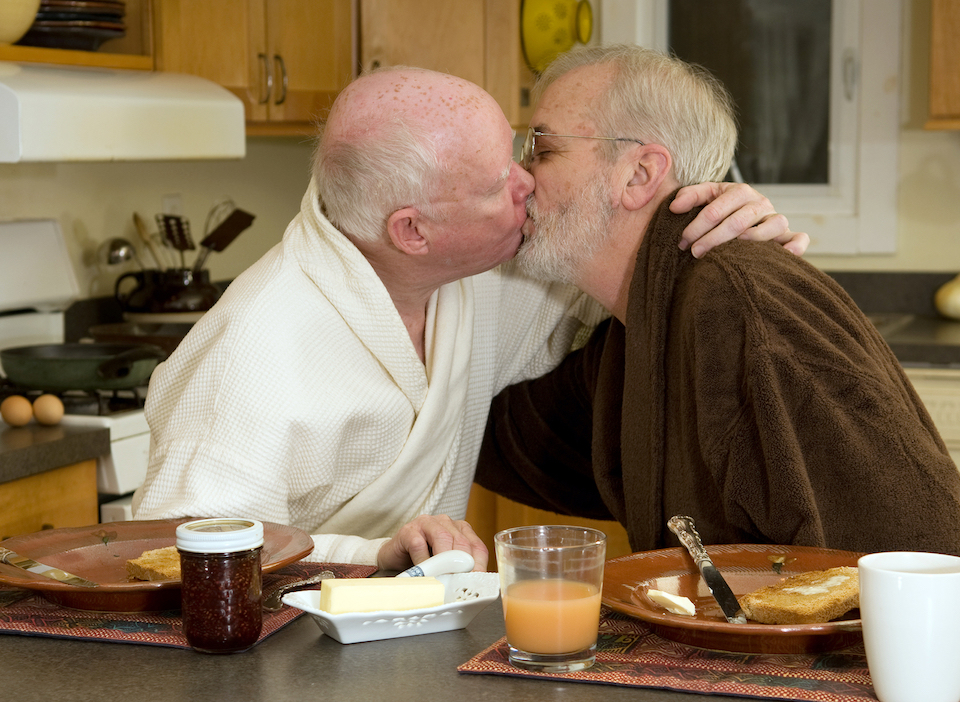

Here, Dr Simon Rosser and Dr Bill West, coauthors of several chapters in “Gay & Bisexual Men Living with Prostate Cancer,” answer 12 questions and offer advice to gay and bi men facing prostate cancer. Simon and Bill are married, out and living with prostate cancer.

1. How common is prostate cancer in our community? Prostate cancer is the #1 invasive cancer for men and the most common cancer in the gay male community. One in seven gay men will be diagnosed in their lifetimes. Since gay male couples have two prostates, they have twice the risk than heterosexual couples or a one-in-three chance.

2. What are the symptoms of prostate cancer? Prostate cancer typically develops without symptoms which is why it needs to be detected through a blood test (the Prostate Specific Antigen or PSA test) and by a doctor feeling for any abnormalities during a digital rectal (or finger up the butt) exam. Two common prostate problems should not be confused with prostate cancer. As we age, our prostates typically get larger which can lead to problems urinating. This is called benign prostatic hyperplasia or BPH. Prostatitis refers to when the prostate gets infected or inflamed.

3. So, what causes prostate cancer? Older men, men with a family history of prostate cancer, and black men are at greater risk of diagnosis and/or worse outcomes. Our research indicates that HIV positive men and bisexual-identified men have worse outcomes than HIV negative men and gay-identified men, respectively. Gay “lifestyle” factors – such as being gay versus straight, lots of sex or no sex, amount and rigour of receptive anal sex, smoking, drug and alcohol use, a history of sexually transmitted diseases and long-distance cycling – have not been associated with greater risk or worse outcomes.

4. So, why is prostate cancer in gay men an issue? Different prostate cancer treatments have different effects on our sexual functioning. About 20 per cent of patients treated with radiation experience radiated bowel, which makes receptive anal sex painful to impossible. Conversely, almost all men treated with surgery (and many with radiation as well) will have erection difficulties, after treatment, making insertive sex very challenging. Treatment can also affect penis size, ability to ejaculate, the experience of orgasm, pleasure in receptive sex, and urinary problems during sex or at orgasm. This makes it important to discuss gay sex with your specialist as part of choosing which treatment will have the least side effects for you.

5. If I want to be checked for prostate cancer, what should I know? The typical test for prostate cancer involves both a blood test and a digital rectal exam. Because massage of the prostate may hypothetically affect the blood results, we recommend you refrain from receptive anal sex or other anal stimulation for 48 hours before the blood is drawn and make sure the blood is drawn before the digital exam.

6. Does being diagnosed mean you have to be treated? No. Many men with low-risk prostate cancer never need treatment. Instead, they go on active surveillance. This simply involves having a blood test every three months to monitor the amount of prostate-specific antigen in their blood. This may also involve additional biopsies to track if the cancer is changing.

7. Is prostate cancer contagious? No, if your boyfriend, husband or a male sex partner has prostate cancer, you cannot get it from him. Prostate cancer is not sexually transmitted.

8. What’s it like to be diagnosed with prostate cancer? Fortunately, prostate cancer has an excellent (over 99%) survival rate provided it is treated early. We are a male couple where both of us have been diagnosed. Here’s what to expect. The initial diagnosis can be scary and requires a biopsy which can be uncomfortable. Don’t panic. Most prostate cancer is slow growing so in many cases you can go at your own pace. Gay men are more likely to feel isolated or go through treatment alone, so it’s important to reach out for support. Prepare a list of questions before each consultation and ask them at your next visit. Bring your man (if partnered) or a friend (if single) to the consultation, both for support and to listen to what the specialist says. Deciding if you need treatment and what treatment is best for you are critical milestones, where many patients seek a second (or third) opinion.

9. How does it affect being gay? Because it’s cancer and because it affects our sexual functioning, many gay prostate cancer patients report feeling less than other gay men. There’s a stigma to having prostate cancer which can affect our sexual self-esteem, sense of attractiveness and potency. And because it affects erections, some men may become more at risk for HIV if their erections are not strong enough for condoms or if they decide to bottom more instead.

10. What’s gay sex like after treatment? Everyone is different. In our experience, good sex is definitely possible after treatment but it is challenging. It takes time and patience (up to two years post-treatment), commitment to sex as a priority, good communication between partners, lots of sexual rehabilitation exercises, and flexibility. The biggest loss we had to deal with was spontaneity – erections don’t just happen, and we have to plan sex if it is to be successful. We found erectile drugs and vacuum pumps to be a help as well.

11. What should I think about in choosing a specialist? Know that many urologists and oncologists see themselves as technologists focused on survival. Not all are good at talking to patients or discussing sex. While survival is obviously important, quality of life is as well. Most gay and bisexual men are sexually active and want to remain so after treatment. So, it’s critical to find a specialist you can be open with, and have your questions answered. When making an appointment, ask for a specialist who is comfortable discussing the sexual effects of treatment. And if they seem uncomfortable or unknowledgeable about sex between men, seek a second or third opinion until you find someone you can trust.

12. If I’m gay, bisexual or a man who has sex with men living with prostate cancer, where can I get help?

For more information: See our just-published book, J. M. Ussher, J. Perz, B. R. S. Rosser, Gay and Bisexual Men Living with Prostate Cancer: From Diagnosis to Recovery (Harrington Part Press, New York 2018).

Book webpage: https://harringtonparkpress.com/gay-bisexual-men-living-prostate-cancer/

For support services: www.Malecare.org is the largest provider of online support worldwide and has groups specifically for gay and bisexual prostate cancer patients.

To get involved in research: At the University of Minnesota, we are conducting the first, large, NIH-funded study testing online rehabilitation designed by and for gay and bisexual prostate cancer patients living in the US.

See: www.restorestudy.umn.edu or email: Restorestudy@umn.edu.

Dr Simon Rosser is a gay men’s health researcher and Dr Bill West a health communication specialist at the University of Minnesota. They specialize in prostate cancer in gay and bisexual men.

They co-authored several chapters in J. M. Ussher, J. Perz, B. R. S. Rosser, Gay and Bisexual Men Living with Prostate Cancer: From Diagnosis to Recovery (Harrington Park Press, NY, 2018).

They are married and out as a gay couple living with prostate cancer.